Why did it take so long for prediction markets to find product-market fit?

7 explanations

The Iowa Electronic Markets pioneered the first modern instantiation of a prediction market in 1988, allowing academic researchers to trade contracts on political outcomes. DARPA experimented with prediction markets for intelligence gathering through its Policy Analysis Market in the early 2000s, but was quickly shut down due to some markets being associated with assassination markets of political leaders.

Companies like Google and Microsoft have experimented with internal prediction markets to forecast project timelines and product success. InTrade emerged as one of the first major public platforms, gaining attention for its accurate predictions of elections and other events before shutting down in 2013. Augur launched in 2018 on Ethereum but struggled to gain traction.

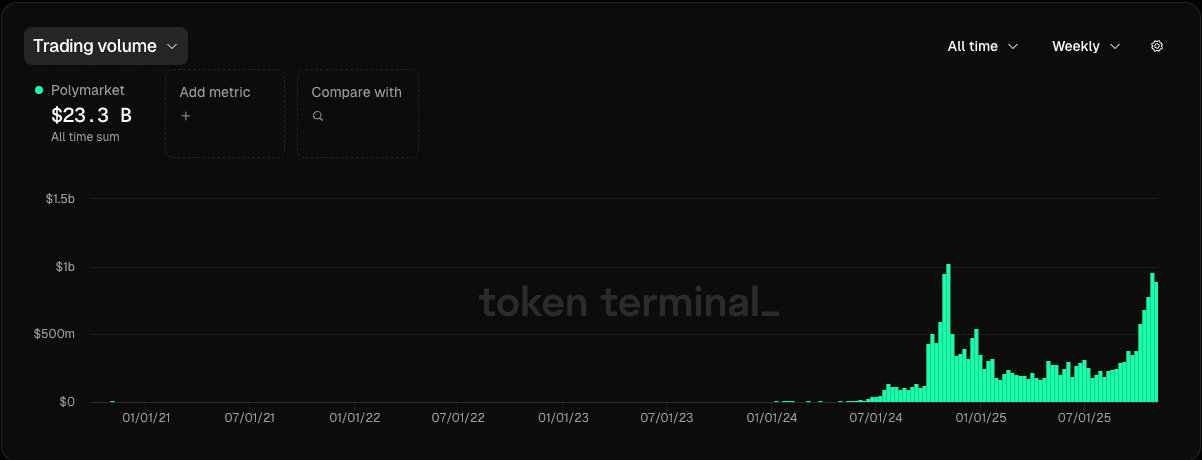

In 2020, Polymarket did $11.3M of volume during the week of the 2020 US presidential election and had effectively zero volume until 2024.

Various implementations of prediction markets have been attempted over the past decades. Yet they only achieved cultural product-market fit within the past year.

Today, prediction markets process over $3 billion weekly. New partnerships emerge daily to integrate prediction markets into sports, news, and search.

In this post, I provide seven explanations, ranked from most to least likely, for why prediction markets took so long to find product-market fit.

1. US regulatory agencies outlawed the creation of prediction markets.

The CFTC effectively banned prediction markets for decades through aggressive enforcement. InTrade shut down in 2013 after regulatory pressure. Augur launched in 2018 but struggled to gain traction, partly because operating in regulatory gray areas limited legitimate user acquisition. The few attempts to obtain licenses faced years of legal battles with uncertain outcomes.

Sophisticated participants (traders, market makers, institutions) avoided unlicensed platforms due to legal risk, instead opting to trade correlated assets or one-off event contracts OTC. Without sophisticated participants, markets remained thin and poorly priced. Without good prices, platforms couldn't demonstrate value to regulators.

Instead of providing licenses for prediction markets, the government reluctantly allowed sports betting because it is much easier to monitor sports markets where the counterparty is a single entity (DraftKings, FanDuel, etc.). It is much easier to shut down a known entity they interface with than an exchange with unknown participants.

2. Both sports betting and crypto were necessary pre-requisites to enable prediction markets.

Sports betting normalized real-money event speculation. Before widespread legalization (post-2018 in the US), gambling maintained cultural taboo status. DraftKings and FanDuel spent billions on advertising, making it socially acceptable to directly bet on real-world event outcomes.

Crypto solved the bidirectional payments problem without regulatory approval. Black Friday (April 15, 2011) shut down major poker sites and seized player funds. The Department of Justice indicted poker sites including PokerStars, Full Tilt Poker, and Absolute Poker for bank fraud and money laundering. Crypto primitives, specifically stablecoins, allowed Polymarket to leverage onchain USDC to enable seamless deposits and withdrawals on Polymarket.

Polymarket processed $3.6 billion in volume during the 2024 election cycle while operating outside traditional finance. This forced regulators to acknowledge market demand. Kalshi was able to receive CFTC approval more easily after Polymarket demonstrated product-market fit and the willingness to play ball with regulators.

3. The talent required to build a good prediction market had higher EV opportunities elsewhere.

Building a prediction market requires the same skill set as building a traditional brokerage or crypto exchange: order matching, liquidity management, market making, etc. The builders who possessed these skills had more attractive options.

Notably, both SBF (FTX) and Jeff (Hyperliquid) built prediction markets as their first foray into crypto. Traditional exchanges have proven demand, clear revenue models (trading fees on high-volume assets), and established regulatory frameworks.

Competing with Robinhood, Coinbase, Binance, or Hyperliquid is much more difficult today due to network effects. The next generation of builders naturally seeks adjacent opportunities with less established competition, and prediction markets remain a logical underexplored market opportunity.

4. The core constituency of traders was too young to trade prediction markets.

The most popular markets on Polymarket only have around 1,000 traders. Prediction markets resonate with a generation raised on MMORPG economies, esports, crypto, and Twitter.

This generation only reached maturity over the past 5 years.

5. Binaries are not a very attractive market structure for market makers without sufficient proven retail demand.

Binary outcomes create extreme adverse selection risk for market makers posting quotes on an orderbook. A single piece of news can move prices to 0 or 100 instantly, and it is difficult to hedge risk accordingly.

The infrastructure and resources required to provide liquidity on prediction markets was not worth the cost, especially since there was no proven demand by retail users. This is evidenced by SIG losing money providing liquidity during Kalshi's early days where their counterparties were informed traders.

6. The demand for truth is vastly greater today than in the past, and prediction markets are another tool for uncovering truth.

Trust in national mainstream media has fallen by over 20 percentage points over the past 10 years. Because people used to trust mainstream media more, there was much less demand for prediction markets.

This demand for aggregated truth mechanisms did not exist when institutional trust remained high. Twenty years ago, most people trusted major newspapers and academic forecasters. Today, prediction markets serve as infrastructure for navigating epistemic uncertainty in a lower trust society.

7. Prediction markets don't actually have product-market fit.

I don't believe this to be true, but it is worth playing devil's advocate.

It is possible that prediction markets don't actually have product-market fit and their volume is heavily distorted by the liquidity incentives given out by the platforms.

The same claim could have been made during the early days of Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash. In 2010, it was unclear if the unit economics would work out and existed in a regulatory gray area for many years.