Don’t Build an Audience

Great work always finds the people who matter

On his podcast with Scott Alexander and Daniel Kokotajlo, Dwarkesh makes the claim that everything that is good gets read by all the right people:

“I feel like this slow, compounding growth of a fan base is fake. If I notice some of the most successful things in our sphere that have happened; Leopold releases Situational Awareness. He hasn’t been building up a fan base over years. It’s just really good…I mean, Situational Awareness is in a different tier almost. But things like that and even things that are an order of magnitude smaller than that will literally just get read by everybody who matters. And I mean literally everybody.”

Scott responds with:

“Slightly pushing back against that. I have statistics for the first several years of Slate Star Codex, and it really did grow extremely gradually. The usual pattern is something like every viral hit, 1% of the people who read your viral hits stick around. And so after dozens of viral hits, then you have a fan base. But smoothed out, It does look like a- I wish I had seen this recently, but I think it’s like over the course of three years, it was a pretty constant rise up to some plateau where I imagine it was a dynamic equilibrium and as many new people were coming in as old people were leaving.”

Watch the full clip here: Dwarkesh Podcast

The underlying assertion that Dwarkesh is making is that the content market for ideas is very efficient. Scott agrees conceptually but to a much lesser degree, citing his own experience in the early days of Slate Star Codex, and indicates that he considers the market to be less efficient than Dwarkesh does.

As a recovering efficient markets believer, I am very skeptical of anyone claiming that any market is efficient. However, Dwarkesh is correct here. Stated precisely:

The content market for novel and interesting ideas is efficient, enabled by incentive-aligned market microstructure.

To avoid ambiguity, let me define exactly what I mean by that claim:

- Content markets refer to markets that operate on internet rails. They have zero or effectively zero marginal cost and are non-rivalrous.

- Efficient means optimally connecting suppliers (content creators) in such a way that maximizes consumer satisfaction. People are bounded by their time and care about consuming the best ideas and content.

- Market microstructure refers to the mechanisms, tools, and systems that govern how content is discovered and distributed. [1]

In simple terms, good work gets noticed by everybody who matters.

Doesn’t Scott Alexander disprove the efficient content market thesis? Slate Star Codex is one of the most influential blogs ever and it took years for it to take off.

Short answer: no.

Scott is one of the best writers on the internet. For the efficient content market thesis to hold, at least one of the following has to be true:

- His early blog posts are not that impressive.

- The blogging market microstructure was severely under-developed in the early 2010s.

After going through his early posts, while well-written, they hadn't yet developed the unique insights that would later define his influence.

Many posts are interesting in hindsight because they provide insight into what Scott was thinking about in the early days. But reading the blog posts in a vacuum, nothing particularly stands out.

What does stand out is Scott’s consistency. In his first year of blogging (2013), he published 157 posts totaling more than 150,000 words. His writing frequency meant that he had a large volume of attempts to improve and eventually land 2+ standard deviation banger posts:

- The Control Group Is Out Of Control

- I Can Tolerate Anything Except The Outgroup

- Meditations on Moloch

(There are too many to list)

Blogs are compression machines: quality content requires a minimum amount of contextual surface area to support in-group references and insights. Marc Andreessen, Paul Graham, and Tyler Cowen all had pre-existing social capital and reputations. Bootstrapping a blog, especially as a nobody, is difficult and typically requires a minimum number of words to demonstrate insight. Scott had little context or reputation to draw from (he had some reputation from prior forum posts) and had to derive everything from scratch.

Most posts by anybody who blogs with any regularity are not insightful and subsequently forgotten. Volume enables more shots on goal to generate truly quality posts that generate outsized discussion and shape downstream culture:

- Why Software is Eating the World

- Do Things That Don’t Scale

- The changes in vibes – why did they happen?

Regarding (2), I don’t have first-hand insight on the blogging scene and infrastructure during this time (I was a much younger lad). I am hesitant to draw too many conclusions based on second hand accounts. It is clear that the infrastructure is better and operates more efficiently today via better tools and clearer Schelling points than what existed twelve years ago.

Liquidity providers have aligned incentives

Content markets are only efficient insofar as there are liquidity providers to efficiently serve content to interested end users. Liquidity providers can either be people or an algorithm. Both operate with an implicit or explicit bid-ask: the ask is the quality threshold of what they are willing to promote while the bid is what the audience expects. Cross the spread to gain exposure to their audience.

There are two ways for your content to gain immediate traction: somebody references it or an algorithm serves it. Both provide liquidity to your content, distributing it to interested consumers.

If you write something amazing, a few emails to some key people in your field is all you need to start this process. These intellectual liquidity providers are highly incentivized to reference your work as they (1) prove to their audience that they are still capable of identifying good content from talented individuals and (2) receive goodwill from you. This may lead to downstream events such as letting them invest in your startup or meeting your peers with other interesting ideas.

Dwarkesh is popular because of his ability to have deep, frontier-pushing conversations with extraordinary people. Tyler Cowen is popular because of his ability to identify nascent ideas and early signs of talent. After filtering for any junk, he’s incentivized to throw a link up on Marginal Revolution for association and attribution. Alexey is popular because of his ability to provide compelling evidence that people in storied institutions are deceiving us and also that he’s good at identifying developing technical talent.

Algorithms like the YouTube algorithm seek to maximize platform engagement. Platform engagement is highly correlated with the amount of interesting material a user receives. Early versions of algorithms were heavily weighted to serve new content from large existing content creators. On average, a post from a creator with a large following is much more likely to be engaging versus the marginal creator with no track record. This is a tractable signal of a creator’s quality that is easy to implement as a model feature.

TikTok's innovation is its algorithm that serves content to end users without heavily indexing on a creator's pre-existing following. Substack is attempting to replicate this model for text, actively improving discovery via a similar algorithm. Aside from specific forms of content regulated by governments, algorithms are not incentivized to discriminate against you in the long run, as they would lose out to a more efficient algorithm that serves users with better content.

While your ideas and blog won’t market themselves, the actual effort required is extremely minimal. It takes literally 30 minutes to write a few emails and post on the platforms where your desired consumers are.

There are more than enough rational liquidity providers to make this market very efficient, which is why I don’t buy a survivorship bias argument. Instead, content doesn't take off because it either isn't as exceptional as initially believed or lacks sufficient initial distribution effort.

Increase your banger base rate

An aspiring content creator saying, “I want to build an audience” is as much of a countersignal as an entrepreneur saying, “I want to be rich”. It’s vain and demonstrates no insight on how to actually achieve their goal. Worse, they consciously create content based on this framing via backward induction, a one-way ticket to the 0-view content graveyard.

Any insights you generate can be efficiently and widely shared with attribution regardless of whether you have a pre-existing audience. [2] Popularity in content markets reflects the aggregate probability that you'll produce power law content. Each additional piece of evidence of your ability to generate new ideas or insights will increase your banger base rate. If you come out of nowhere and one-shot Situational Awareness, the market prices you as having a 1/1 hit rate. People are incentivized to follow you on Twitter, subscribe to your blog, and watch your podcast appearances to seek out any other insights you have.

The early days are the best

One of my favorite things to do is to read through the blogs and tweets from people before they became widely recognized (paying special attention to which posts they backlink to and who is in the comment section). For a select few, I’ve been fortunate to have a front row seat throughout their entire journey. Whether they are videographers, writers, or programmers, they dug themselves out of the early trenches, connecting with their audience and finding their voice by consistently producing content.

When you’re a nobody, you get a zero-noise signal via metrics including likes, comments, retweets, and views. When you gain followers, even terrible content gets likes and comments from your followers giving you unearned dopamine and a false sense of accomplishment. Worse, you might even start to write pandering slop posts that you'll have to pay back down the line, or you'll decay into obscurity. It makes me very sad to see some of my favorite writers follow this trajectory and actively decay in real time.

Lucky for me, I’m still an obscure nobody. Most of my posts get very few views, floating in the digital ether as unread bits in some us-east S3 bucket.

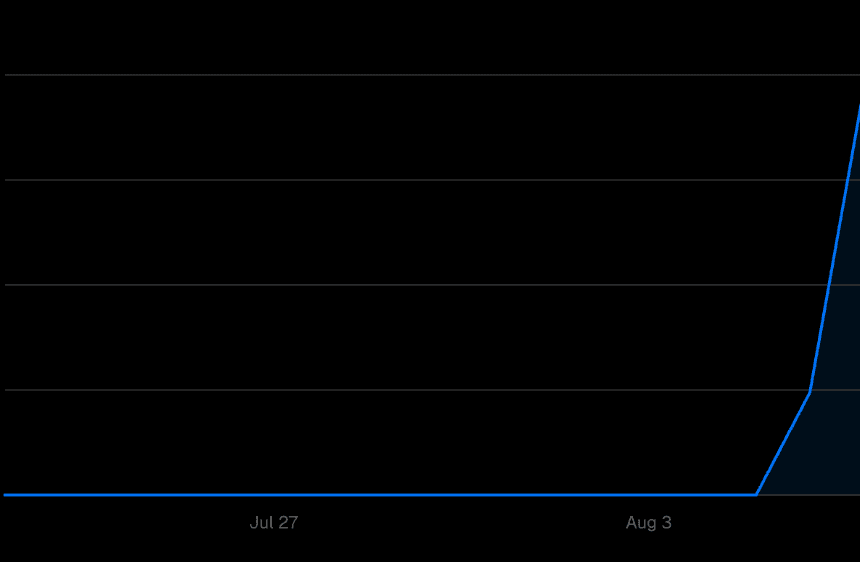

My third post, No One is Really Working, is the one exception, at least relative to my other posts. That post blew up primarily thanks to Alexey Guzey’s tweet. It was up for 135 days before his tweet with de minimis viewership.

You'll never guess what happpened after

(If any of my other posts were any good, they would have gained recognition. I can definitively tell you that lots of people read my earlier posts. They just weren’t very good.)

When I was messaging with Alexey a couple days after it blew up, he mentioned that he did not expect that level of virality. Furthermore, he said that after his many years of blogging and Twitter, he still is not able to predict which ones will blow up with any meaningful degree of certainty.

With all due respect to Alexey, I disagree. I believe I have enough data and taste to predict which pieces will do well and which won’t ex ante.

From this post forward, each post will include a hash of my prediction for each post’s performance to test this thesis. I will analyze the results in a future post.

375fe6f5ad8993c980f7661fea4839edb591100494d4a1b8f0271c3b9ad5752a

[1] The rise of Substack is the most influential development in the written content market, aggregating content into a centralized, searchable site. Algorithms can then be trained on its data to serve the best content to end users on an individual basis. Furthermore, Substack is built on permissionless, portable substrate: email. This limits their ability to create a walled garden and incentivizes long-term actions. Obviously this centralization comes with many drawbacks including increased homogeneity.

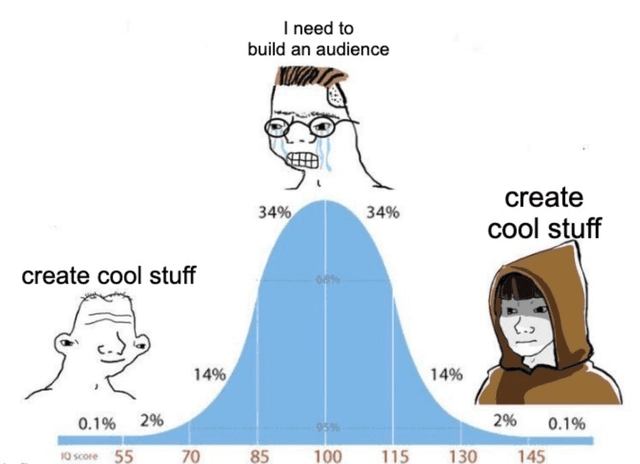

[2] This entire post can be summarized by the following graphic: