Never Reason from a Price Change, Culture Edition

Save us, Sumner

Every so often in conversation, I’ll hear someone say:

- “People aren’t buying gas right now because the price is high.”

- “People aren’t buying houses now because interest rates are high.”

- “Everybody’s wages are rising, which causes inflation.”

Every time a statement like this is uttered, a piece of Scott Sumner dies inside.

Sumner has a famous meta-insight: “Never reason from a price change”. The principle references instances where people treat prices (outputs) as causes rather than effects. When we observe a price change, it's always the result of underlying shifts in supply, demand, or both. The price itself tells us nothing about which force is at work. Responses should target the cause, not the symptom.

If you haven’t studied economics or really thought about these issues, it’s understandable how one could fall into these traps. Ceteris paribus, you typically buy less of something when the price is high and more of something when the price is low. But prices here are the effect, not the cause.

But it’s not just the random layperson making these mistakes. Sumner cites famous, well-seasoned economists making these errors:

- Robert Shiller viewing low real interest rates as an incentive for investment

- Larry Summers equating low interest rates with easy monetary policy

The correct interpretation of each statement is:

“People aren’t buying gas right now because the price is high.”

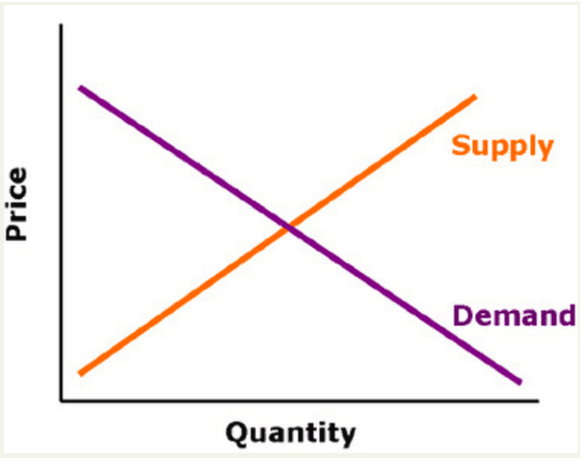

Markets operate via supply and demand. Consider the most basic Econ 101 graph:

Price is the y-axis, or the effect. The price of gas can cause lower and higher consumption based on different input factors:

- An Arab oil embargo caused higher prices and lower consumption in 1974.

- Booming Chinese auto sales caused higher oil prices and higher consumption in 2007.

Prices are not a cause of anything; they are an effect.

“People aren’t buying houses now because interest rates are high.”

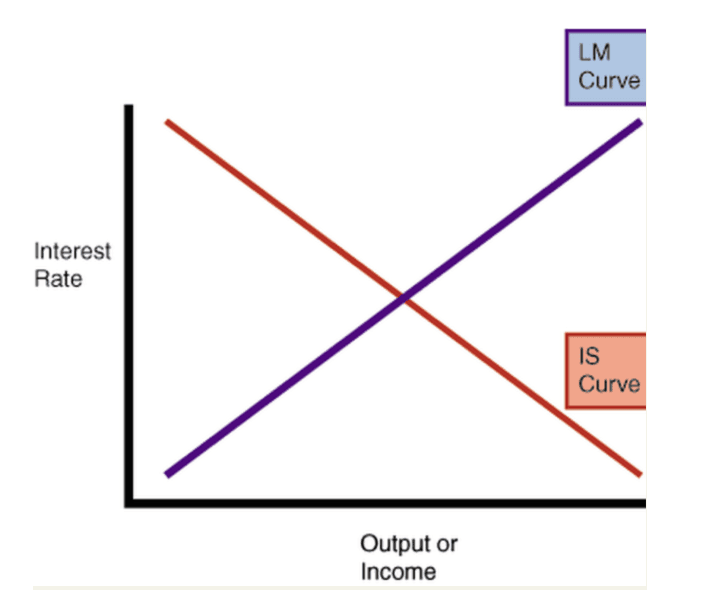

In credit markets, high interest rates can be caused by more demand for credit or less supply of credit. Graphically, it is represented by the IS-LM curve:

Low interest rates can be caused by less demand for credit (IS shifting left) or more supply of credit (LM shifting right). Only in the latter case would investment be expected to increase.

Worse, high interest rates have been empirically caused by shifts in the demand for credit, not shifts in the supply in credit. And yet many people, well-trained economists included, still mistakenly conflate high interest rates with low investment.

“Everybody’s wages are rising, which causes inflation.”

Wages are the price of labor. One cannot explain one price change (consumer prices) by pointing to another price change (wages). Both are downstream from shifts in monetary conditions.

Wages can rise due to:

- Monetary expansion: The Fed increases money supply, causing both wages AND prices rise together as the new money circulates through the economy.

- Productivity surge: Worker output increases, causing wages rise to reflect higher marginal product, but prices falling as more goods chase the same money.

Just as prices are signals rather than causes, many observable social phenomena are outputs of complex systems, not inputs we can reason from directly. So many statements and situations in life fall victim to this same trap:

- Crime rates are falling, therefore cities must be safer.

Lower reported crime does not necessarily translate to safer streets. Reporting practices, policing intensity, and advances in trauma care can all reduce recorded crime without reducing dangerous incidents.

- What’s popular on Twitter and Reddit is indicative of people’s opinions given that Reddit is a public, popular town square.

Virality reflects algorithmic choices and selection effects, not collective belief. Engagement metrics are not evidence of true demand.

- Mental health rates are increasing, therefore more people must be having mental health issues now.

Rising diagnoses could mean more mental illness, or simply that destigmatization enables help-seeking, therapy-speak provides social currency, and the medical-industrial complex incentivizes labeling.

- Declining test scores means that our ability to educate people is decreasing.

Rather, falling test scores could be from the test-taking pool increasing, meaning that the average is dropping because the pool is simply broader.

- People don’t read books because our attention span is cooked.

Book decline might reflect medium substitution, publishing’s quality collapse, or competition from superior storytelling on novel mediums. Economic pressures reducing leisure time could matter more than attention capacity.

- People aren’t having kids because they’re too expensive.

Birth rates fall even in countries with generous child subsidies, suggesting cost isn't the primary driver. Shifts toward self-actualization over family formation (values change), climate anxiety making the future feel inhospitable for children (future pessimism), and contraception fully decoupling sex from reproduction (technology).

The number of extremely sharp people I’ve heard make these mistakes in conversation is astounding. It makes you wonder how often we conflate pattern-recognition with understanding, moving through life without ever examining the mechanisms underneath.

If such errors persist in economics, where there is direct emphasis on systems thinking and causality, what does that imply for the other sciences? Are we even thinking about problems in physics, biology, and other fields correctly?