Hyper-Optimized Children

For many parents, hyper-optimization is the preferred method for brute-forcing their children out of mediocrity.

NBA

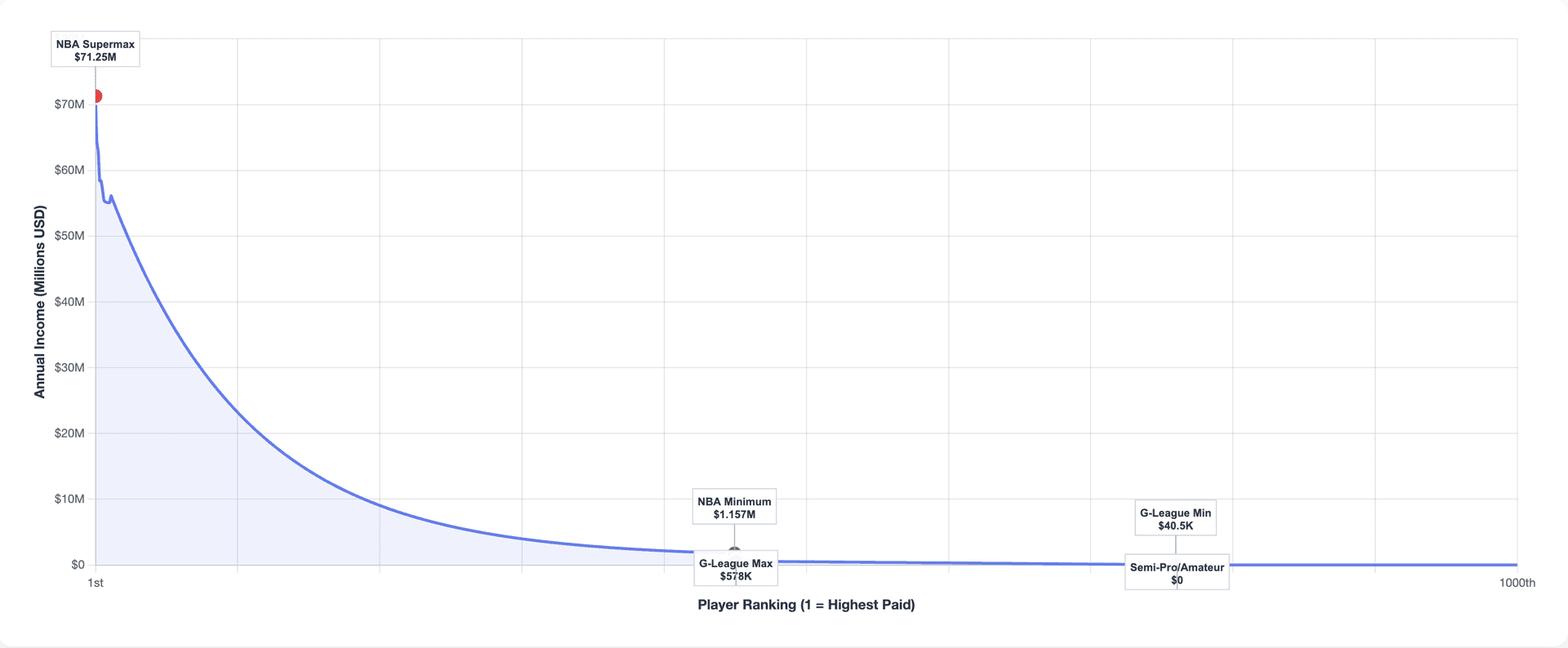

The NBA is one of the most competitive domains in the world. There are 450 active players in the NBA at any given point in time (15 players per team, 30 teams total). The distribution of annual income for the top 1000 basketball players in the world looks something like this:

In the 2024-2025 NBA season, the average salary was $9,191,285, and the median salary was $3,657,120.

With such a steep drop in income and prestige among the top 1000 basketball players in the world, it is no surprise that parents are doing all they can to surpass the 450 threshold and climb along the NBA salary curve to get as close as possible to the NBA supermax.

Young children who have a shot at making the NBA typically show a strong signal from a young age. The baseline attributes include height and athleticism. On-court IQ is becoming increasingly important and better measured with advanced statistics and cameras. These traits are correlated with parents with above-average genetics and the resources to provide their child with the best environment to develop. Parents who are 2+ standard deviations athletic and domain-intelligent are much more likely to have children capable of playing in the NBA.

This is intuitively true and becoming more and more empirically true every passing year in NBA data:

Naturally, these parents want their kids to be successful. When they see that their kid has the genetic makeup to be in the NBA one day, they pour in resources to have their kid achieve that goal. Parents center their lives around enabling their kids to develop their abilities and make the league.

The average NBA player is far more athletic, skilled, and smarter than NBA players just a decade ago. The average NBA player from the 80s would have no shot at being in the league today with how the game is played today. The game itself has been optimized to a local equilibrium of high-volume threes.

Because the skill floor is so much higher today, NBA players are expected to enter the league with a much higher baseline skill set. This is advantageous for kids who have been playing basketball for their entire lives and attending camps with retired NBA players. It is now normal to see kids play AAU, travel ball, and varsity basketball throughout the entire year.

Even the NBA referee pipeline is becoming increasingly optimized.

NBA referees are even more competitive by the numbers. In the 2024-2025 season, there were 75 full-time referees. Referee salaries range from $150,000 to $550,000 per year, not including playoff games and bonuses (or other highly liquid avenues of making money).

Referees spend years watching game film and deliberating on the correct calls for contested plays. With the baseline genetic requirements for a referee being much lower than players, their moat is social barriers and a strong union with storied ties to NBA owners. The NBA is an entertainment product, and the referees with a lifelong understanding of the culture, along with the rich social and tacit knowledge passed down via tight social circles, create a pipeline for the next generation of NBA referees.

At least 14 current or former NBA officials came from Delaware County, Pennsylvania, and strong clusters around metropolitan East Coast cities. Unsurprisingly, their lineage can be traced back to families and friends, and a conscious effort to track the future generation to become seasoned referees.

Ron Garretson was the son of Darell Garretson, the NBA’s first Director of Officials. Joey Crawford officiated over 2,900 NBA games, and his father was an MLB umpire. James Capers Jr. is an active official in the NBA, having officiated for over 28 seasons, and is the son of former NBA official James Capers Sr.

University Admissions

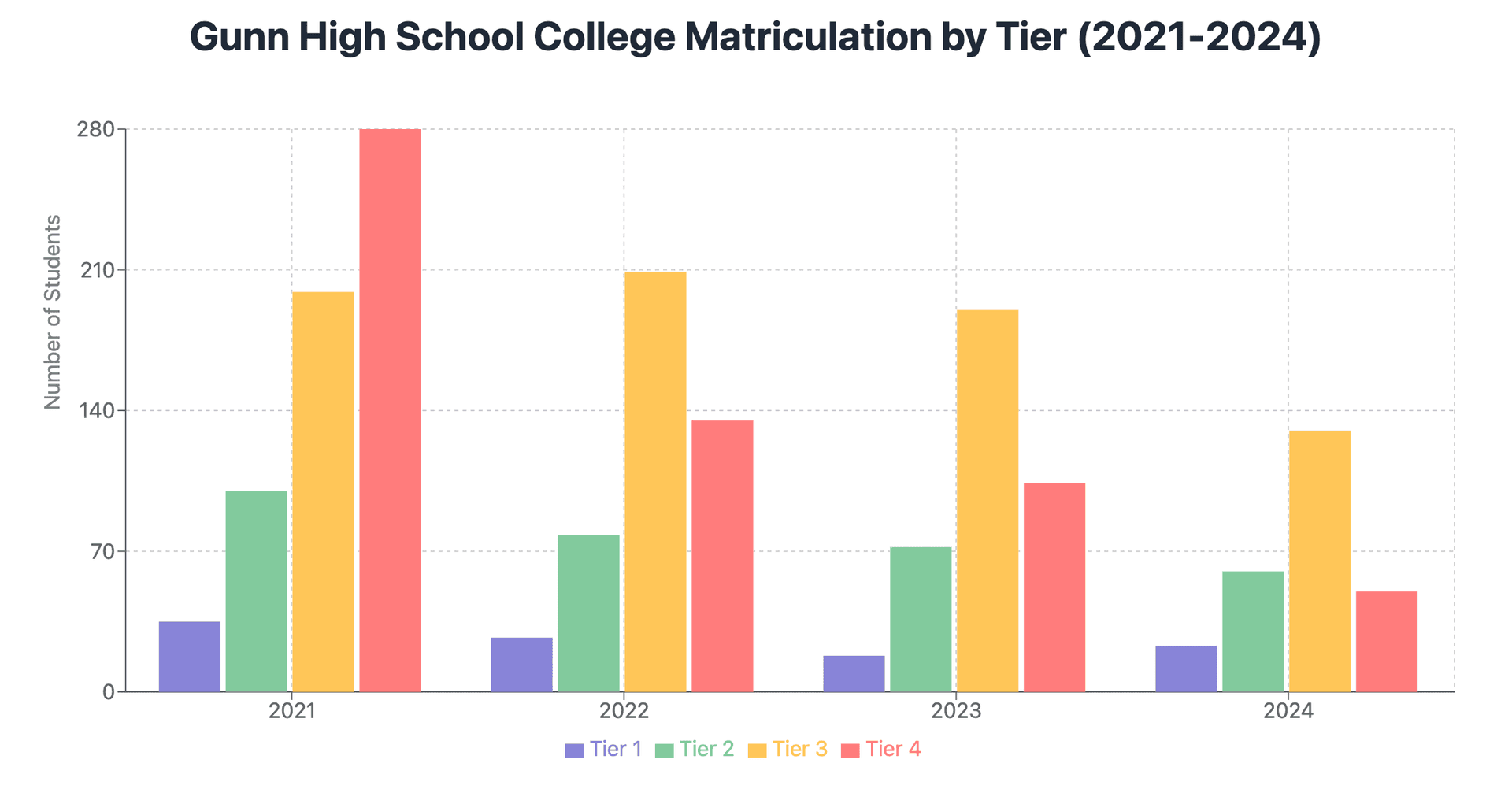

Gunn High School is located in Palo Alto, California, and is one of the most competitive high schools in the country. Located near Stanford, parents disproportionately represent high-status intellectual professions: professors, venture capitalists, software engineers, doctors, and lawyers. It is no surprise that they disproportionately attend prestigious universities with low acceptance rates:

Parents spend resources on SAT tutoring, grinding some sport, and doing some extracurricular activities (speech and debate, robotics, etc.). Parents frequently send their kids to special Pre-College Summer Programs during their high school years to demonstrate more signal to colleges. The next meta includes having their children nominally start companies and non-profits to further distinguish themselves from their peers.

Parents understand that baseline test markers are no longer sufficient for collegiate admission success. To give your child the best chance of success, they must demonstrate excellence beyond their peers in one or more dimensions. Parents’ search function often starts by casting a wide net of potential activities, then doubling down on areas they believe their child has a comparative advantage in. Comparative advantages can arise from natural aptitude (e.g. predisposition towards math) or low-competition environments (e.g. fencing).

Regardless of what Twitter says, universities are still the institutional gatekeepers of intellectual social status. They are where most frontier ideas are exchanged and where lifelong peer groups are formed. With AI researcher compensation now on par with top NBA athletes, one should expect increasingly formalized hyper-optimized funnels to extend beyond college admissions and to a prestigious PhD program or top research lab.

The above examples are cherry-picked and certainly not representative of the median case.

But they illustrate the lengths parents will go to for their children and the natural progression of the professionalization of talent funnels. When the pathway is legible, you can bet that professional pipelines will emerge on the promise of getting your kid into the desired elite.

These pipelines exist because of the following factors:

- The number of high-status positions has remained relatively constant.

About 2,200 high schoolers were admitted to Harvard’s Class of 1982, 2,147 in 1992, 2,074 in the mid-2000s, and 1,980 for the freshman class of 2021. During this time, Harvard went from ~10,000 applicants to over 54,000. Cornell, Dartmouth, Brown, and Yale have only seen a modest 20% growth in class size (~400 students).

On the faculty side, Harvard has plateaued at 720-730 ladder faculty (tenure and tenure-tracked) since 2008 despite large endowment growth. Faculty growth stagnation continues to persist at the vast majority of institutions.

- Returns are compressing to select elites, with a steep drop-off.

The 451st best basketball player and the 781st best baseball player are scraping by in the minor leagues. The best engineer at a low-tier contracting agency is making significantly less than the worst full-time engineer at a tech company.[1]

- Parents are having fewer children and investing more per child.

The US fertility rate has fallen from 3.5 in 1962 to 1.6 in 2023. Fewer people are having children, and those who do have children are having fewer of them.[2] More resources are being invested per child.

High-achieving parents who are on the tail end of the power law outcome will naturally want to do everything they can to increase the likelihood that their kids are positioned to do the same. They are incentivized to give them every unfair advantage to stack the deck in their favor. This ever-increasing anxiety not to let their children fall through the cracks of society creates more demand for optimizing their children.

- The incentives of parents and children are not 100% aligned.

Parents act as insurance for their children. They invest resources in the early years with the goal of having their kids be self-sufficient in their 20s. Parents are on the hook emotionally and often financially if their kid is a deadbeat or goes broke building a startup. Even in the success case, parents benefit sublinearly from a large increase in their children’s wealth.

Their children are more incentivized to go after the extreme power law outcomes. This is especially true for high-ambition kids heading down a path that leads to a similar life to their parents, as they naturally aspire to have a better life than their parents. If they succeed, they propel themselves to new social circles and financial heights. If they fail, their parents are there to catch them.

This creates the incentive for parents to go after clearly defined, high-probability opportunities. Their children are incentivized to take more risks in hopes of punching their ticket into the upper echelons of the elite. Unlike the current high-status thing, the signals to get into the next-generation elite are amorphous and typically don’t have pipelines. Nobody was sending their kids to creator camps in 2010 or teaching them how to be a good online poaster.

Kids grow up aspiring to be the next Michael Jordan; parents just want to make sure they land somewhere in the middle of Google’s org chart.

Hyper-Optimization is Individually Rational But Collectively Insane

From the outside, all this sounds pretty depressing and dystopian for what is supposed to be the most prosperous time in human history. Hyper-optimization creates cohorts of zombies operating as vessels for their parents’ ideas of success. This is why it’s always so refreshing to meet someone who didn’t start coding when they were 5, do three sports, speech and debate, all while “starting a nonprofit” for African kids from their modest home in Atherton.

Children intuitively know how much their parents are investing in them, even at a young age. They don’t want to let them down, but their parents’ expectations are so much higher and the competition is so much better that they get sent down this rabbit hole that they had no choice in selecting. Trapped by this large sunk cost, most do not stray from the prescribed path, choosing the path of least resistance as they are anesthetized into a replaceable, homogeneous career where no one is really working. Parents think they're brute-forcing their children out of mediocrity when they're actually brute-forcing them into it.

Talent can emerge from unexpected places: Nikola Jokic developed his game from northern Serbia, and many elite programmers bypassed the Bay/Waterloo/Boston/T-20 pipeline entirely. The failed simulation effect – when we can’t quite mentally simulate how a person got to where they are – sends such a strong signal because they acquired their skills under atypical circumstances. More importantly than the skill itself, they demonstrate genuine motivation, free from their parental anxieties and expectations. Anecdotally, they are more curious, oftentimes more friendly, and more likely to view the world as positive-sum.

Hyper-optimized children are a luxury and largely a developed world phenomenon. The countries with hyper-optimized children en masse and respective tracked industries are some of the least creative and least happy. These countries – Korea and Japan in particular – are insanely zero-sum and inward-looking. Furthermore, each generation’s worldview narrows to the tiny slice of the human experience that exists within their hyper-optimized bubble.

We've successfully built a machine that turns curious children into anxious adults. Everyone knows it’s broken. No one knows how to stop.[3]

[1] The financial payouts for SWEs are much more linear than professional athletes, but the point is that it is still a piecewise function.

[3] Well, Bryan Caplan has one solution, and it’s to just be more fatalistic about people’s potential. He argues that nature accounts for more than we think, and nurture via overbearing parenting is very overrated. The natural corollary is that one should have more kids for the highest chance of a positive outlier. I don’t think this ideology has a chance to become popular amongst any meaningful part of society, particularly those from immigrant backgrounds.